Fasciola hepatica is widespread across Europe affecting cattle, sheep and goats and is only absent in areas where its snail vector is not present, which are the chilliest northern latitudes in parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Iceland. The prevalence of this liver residing parasite varies from country to country, and it finds its sweet spot for optimum survival in wet, temperate pasture regions, like those seen in Ireland, Western France, the UK, Northern Italy and central Europe.

Fasciola hepatica has an indirect lifecycle and uses mainly the snail species Galba truncatula in Europe as its intermediate host. Fluke eggs passed in the faeces start to develop and when the egg is exposed to stimuli of increased light and temperature a miracidum is released. This miracidium requires water to swim to find a snail and when it finds a suitable snail it burrows through the foot and into the snail’s body. The miracidium develops into cercariae which the snail releases over a period of time, again dependant on optimum temperatures. These cercariae encyst out on pasture and become infective metacercariae. When a grazing animal ingests these, they hatch and burrow through the gut wall, migrating to the liver. These immature flukes continue their migration through the liver to the bile ducts over 6-8 weeks. On arrival in the bile duct they mature and start producing eggs that are shed in the faeces.

Snail, rain or shine: The seasonality of Fasciola hepatica infection

Historically Fasciola hepatica infections were linked to the seasonality of snail activity and so therefore were mainly a summer and winter infection. Summer infection of snails occurs from May to July with the snails then shedding massive numbers of cercariae onto pastures in July to October with resultant disease seen in animals in late summer to early autumn.

Snails infected towards the latter end of the year tend to hibernate over winter, reemerging the following spring shedding cercariae onto pasture. This can cause unexpected disease earlier than anticipated that year. Snail activity is very temperature dependant and liver fluke forecasting by national authorities is useful in planning a parasite control programme and forecasting potential periods of peak snail activity.

The welfare and economic cost of Fasciola hepatica infection

The costs of Fasciola hepatica infection are both direct (due to clinical disease) and indirect (through subclinical production losses). The estimated cost in the UK alone on an annual basis is over £31 million and in Ireland it is estimated at €90millon annually. The migrating immature fluke causes acute fasciolosis due to traumatic hepatitis which contributes to weight loss, ill thrift and, in severe cases, death. The acute form is seen more often in sheep.

Chronic fasciolosis results from mature adults residing in the bile ducts of the infected animal. Sheep fluke can live as long as the sheep itself, whereas with cattle after a prolonged period of infection the profound changes in the bile ducts result in an inhospitable environment so few fluke survive beyond 2 years. These adult flukes residing in the bile ducts affect the animal and contribute to pasture contamination. Animals have poor milk yield, ill thrift, poor wool condition, reduced growth rates and reproductive performance. Liver damage can result in liver condemnation at slaughter.

Facilitating Fasciola finding – how do we test for infection?

Diagnosis of liver fluke infection can be challenging and should be made using a combination of clinical signs, abattoir results, grazing history, and testing. Testing often requires a multi-pillar pillar approach, as no one test is considered the gold standard. Coproantigen and serological testing can detect early infections and are highly sensitive, but they require samples to be sent to laboratories, are unable to distinguish between active, post-treatment or historic infections and are expensive.

In contrast to the above testing fluke faecal egg counts (FlukeFECs) are non-invasive, immediate and widely available. FlukeFECs are deemed to be particularly useful heading into winter when animals will be housed and are most likely to have patent infections after summer grazing. Standard faecal egg counting techniques are not used for the detection of Fasciola hepatica eggs as they are heavier than other eggs and do not float in standard flotation fluid. A faecal sedimentation test is used in most laboratories to detect Fasciola hepatica eggs, however this is laborious, requires technical training and a large amount of faeces needs to be analysed to improve detection sensitivity.

It’s no fluke that Ovacyte technology has improved FlukeFECs

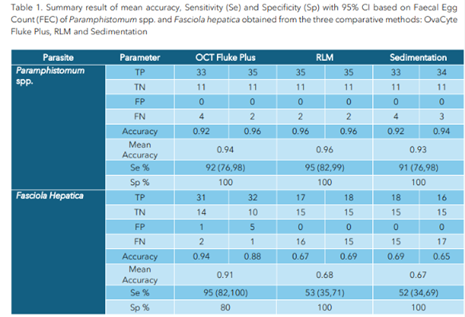

OvaCyte Fluke Plus employs a refined filtration /flotation technique which is more effective than simple sedimentation at retrieving fluke eggs in cattle and sheep. OvaCyte Fluke Plus has an egg detection limit of 1 egg per gram, in comparison to other validated methods with standard detection limits of 10-50 eggs per gram. A comparison of OvaCyte Fluke Plus to two existing validated methods, centrifuge flotation (RLM) and sedimentation, highlighted that

- OCT Fluke Plus proved to be the most effective method for detecting Fasciola hepatica

- OCT Fluke Plus demonstrated high precision in repeatability tests, indicating consistent performance with low variability in the detection of fluke eggs in faecal samples.

Source: Comparison between Telenostic OvaCyte Fluke Plus, Reference lab methods and sedimentation methods of FEC analysis for Rumen and Liver fluke in ovine and bovine faeces, awaiting publication

Source: Comparison between Telenostic OvaCyte Fluke Plus, Reference lab methods and sedimentation methods of FEC analysis for Rumen and Liver fluke in ovine and bovine faeces, awaiting publication

When to use Ovacyte Fluke Plus

Key opinion leaders SCOPS (Sustainable Control of Parasites in Sheep) recommend using fluke faecal egg counts approximately 8 weeks after animals may have been exposed to infective metacercaria. If the result is negative, then retesting 4-8 weeks after is advised.

FlukeFECs are a fundamental tool in diagnosing Fasciola hepatica infections in animals particularly when

- the goal is to confirm active, egg -producing adult infections

- assess treatment efficacy

- monitor herd-level burdens in high-risk periods (e.g. winter housing)

Control of Fasciola hepatica

Sustainable control of fluke on farms involves several key integrated parasite management strategies including snail habitat management, regular diagnostics, pasture and livestock management and judicious anthelminthic use. The SCOPS and COWs websites are invaluable as sources of information, tools and up to date opinions on liver fluke in our ruminants. (links belows)

Beesley, N.J et al (2017) Fasciola and fasciolosis in ruminants in Europe: Identifying research needs’ Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 65(Suppl.1): 199-216

Reigate, C et al (2021) ‘Evaluation of two Fasciola hepatica faecal egg counting protocols in sheep and cattle’ Veterinary Parasitology, Vol 294, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2021.109435

Rufino-Moya, Pablo José et al (2024) Advancement in Diagnosis, Treatment and Vaccines against Fasciola hepatica: A Comprehensive Review, pathogens, 13, 669

Shrestha, S et al (2020) ‘Financial Impacts of Liver Fluke on Livestock Farms Under Climate Change- A Farm Level Assessment’ Frontiers in Veterinary Science, Vol 7 , 564795

https://www.scops.org.uk/workspace/pdfs/fluke-diagnostics-treatment-poster_1_1.pdf

https://animalhealthireland.ie/assets/uploads/2021/04/AHI-Parasite-Control-Liver-Fluke-2021.pdf

https://www.cattleparasites.org.uk/app/uploads/2023/09/liver-fluke-310823.pdf